Summer - L'été

Publié par Brigit Beumers - 23 mai 2018

Catégorie(s): Cinéma, Expositions / Festivals

The End of the Summer Season

Therefore, in many ways this turn to the 1980s is a-typical for Serebrennikov, whilst in line with a number of contemporary art projects and films that address the late Soviet era as a time that inspired hopes for change – reflecting on the present, where such change seems to lie beyond the power of individuals, or the intelligentsia.

In his film, Serebrennikov focuses on the rock musicians Viktor Tsoy and Maik Naumenko in the early 1980s, when the Leningrad rock scene was one of the most vibrant underground cultures in the USSR. Indeed, it was to Leningrad that Nautilus Pompilius (with lead singer Vyacheslav Butusov) would move from Sverdlovsk (as featured in Aleksei Balabanov’s Brother (1997), and where the group Aquarium with bandleader Boris Grebenshchikov was based. The two musicians at the heart of the film – Tsoy and Naumenko – remain less known in the West (than, for example, Grebenshchikov, who recorded an English-language album in London in the 1990s). Maik Naumenko was the founder and leader of the group Zoopark [Zoo], a band that remains obscure for Western viewers. Viktor Tsoy may be somewhat better known to a foreign audience, partly because of his tragic death in a car accident in Latvia in 1990, partly because he had made his reputation also through film, playing Moro in Rashid Nugmanov’s cult film The Needle (Igla, 1988) and featuring in Sergei Soloviev’s ASSA (1987), where he leads the concert of the final scene with the song “We want change” – a cult song of the perestroika generation.

It is on these figures of the rock scene at a moment of juncture that the film focuses. Based on the memoirs of Maik’s wife Natalia Naumenko, Summer is clearly biased and idealises Maik, who is shown ready to give his wife the freedom of having an affair with Tsoy (which she does not) and to abandon the opportunity of recording an album for the benefit of Tsoy, who gets Grebenshchikov’s support. While Maik becomes a martyr, Tsoy is shown in the film as an insecure youth, whose domestic problems with his parents undergoing divorce have been diligently omitted to avoid any claims that may have arisen from the Tsoy estate.

Whilst the film offers a fine portrayal of the atmosphere of the underground rock culture in Leningrad in 1981 – the final years of the Brezhnev era, it also tends towards a harmonized vision of those people who would be the voices of a new generation of protest that would rise with Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of glasnost and perestroika after 1985. The bureaucracy is portrayed here (and in contrast to Soloviev’sASSA) as understanding and supportive, but forced to present the right arguments for their decisions to the authorities. The Afghan war looms in the background. As such, the film makes us think about protest in a rather despairing political context, with possible parallels to the contemporary world. Such a return to the perestroika period seems odd in times of a stable political and economic system, yet it allows a reflection on contemporary culture and make comparisons with the perestroika era as a time when protest could be effective and lead to change.

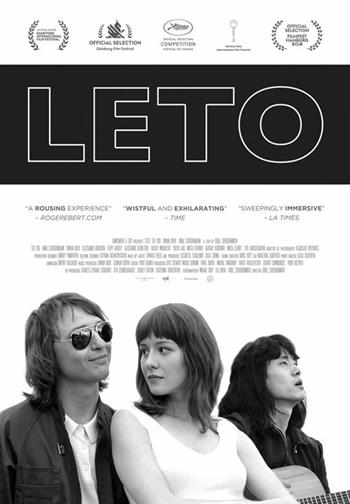

Serebrennikov’s film is shot in black and white, with some colour inserts that look like music clips and serve as explanatory notes, not unlike the footnotes and inserts in Sergei Soloviev’s films. Similarly, there are scenes when animation is used to provide an ironic commentary on the context and the action – again, not unlike the use of such superscript in Soloviev’s ASSA and later films of his trilogy.

Summer is a fine testimony to the time of hopelessness, where a gentle opposition to the system was articulated in the form of songs, lifestyle, informal cultural events and gatherings, but when protest was not yet manifested openly. The wish for a rebellion is not articulated yet – neither in the texts, not the costumes and performance style, nor the wish to try and conform with the performance rules of the rock club. The culture of rebellion is not yet developed, and yet – artists try to voice their views, without any intention of counting on western support. Such a statement has, no doubt repercussions for the here-and-now: as Serebrennikov’s artistic position has been politicised through his views on the mentality of a youth increasingly captivated by fanaticism (see The Student), while he has himself become the victim of the Russian law enforcement, being accused of embezzlement of state subsidies for the Seventh Studio which he runs – alongside the Gogol Centre (a theatre and culture centre) and the Platform (a project base). Serebrennikov has been under house arrest on charges for embezzlement of state subsidies since August 2017, whilst the director-manager and the financial director of the studio have also been arrested, the latter having been detained in prison since May 2017. Serebrennikov had been arrested on the last days of shooting and has edited Summer at home, without contact to the outside world; some artistic decisions, such as the animation for some scenes in a parodic manner, may well be the result of practical considerations where it was not possible to shoot additional scenes.

Summer is an impressive piece by a director who has not himself lived through the late Soviet era, capturing the atmosphere not of despair or false hopes, but of a compulsion to self-express. How much this atmosphere will mean to contemporary European and American audiences remains questionable: many viewers will know neither Naumenko nor Tsoy, and many will probably little about their cult status and the political context. A similar statement might of course be made with regard Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War (Zimna wojna), also playing in competition, where many historical and political details may remain obscure to contemporary viewers. Yet it is this everyday texture of the historical past that intensifies the experience and choices to which the protagonists of these films are exposed.

What Summer lacks, though, is a dramatic conflict. It captures the sunset of a political era and the rise of a new star on the cultural and artistic horizon, without sufficiently linking the two and without motivating character behaviour beyond a sketch. It is a snapshot of a time, which the spectator has to frame and then make the connection to the present – which is maybe a bit too much to ask for from today’s viewers.

Crédit photographique : Copyright Hype Film Kinovista 2018