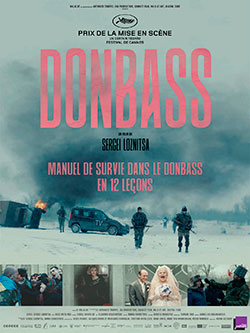

Sergei Loznitsa is an amazingly prolific filmmaker, oscillating between documentary and fiction. Thus, in autumn 2016 he presented his documentary Austerlitz in Venice, closely followed by the fiction film A Gentle Creature (Krotkaia), which screened in competition in Cannes in 2017. In 2018 he premiered the documentary Victory Day (Den’ pobedy) in Berlinale’s Forum, then Donbass opened Un Certain Regard in Cannes, and finally his compilation documentary The Trial (Protsess) received a special screening in Venice. The range of topics that these recent documentaries cover is equally wide-ranging – from an observation of contemporary visitors to the concentration camp in Sachsenhausen and present-day celebrations of 8 May in Berlin to documentary footage of the Soviet show trial of the Industrial Party in 1930. In his two most recent fiction films, which both screened in Cannes, he explores life on the edge of society – a topic which preoccupied also his earlier fiction films (after ten years as documentary filmmaker), namely My Joy (Schast’e moe, 2010) and In the Fog (V tumane, 2012). There Loznitsa focuses on the life of people excluded, for a variety of reasons – from memory loss, war animosity, and crime, from their “native” community. Yet if we expect a continuation of this theme in the new film, which sets out tackle the conflict between ethic Russians and ethnic Ukrainians living in Donbass, we are thoroughly mistaken.

This long introductory paragraph should serve not so much to contextualise Donbass, but to discern some ruptures and continuities in Loznitsa’s work, especially a rupture that I would pinpoint to 2014, the year of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia. Having made two features that explore the role of memory in particular, and a set of finely observed documentaries – of course, as well as several stunning compilations of historical footage, including of the Leningrad siege (The Siege/Blokada, 2006) and the Soviet 1950s (Revue/Predstavlenie, 2008) – we suddenly find a documentary about Maidan (with a special screening in Cannes in 2014) that breaks with the use of historical footage and previous observational strategies to engage locals in the process of reporting. Similarly, A Gentle Creature breaks away from the theme of memory loss or memory distorted by the exigencies of an extraordinary situation, and moves towards a search for truth. A similar can also be detected in the approach to script composition when it comes to Loznitsa’s fictional take on the war in Ukraine, Donbass, which is moves away from a coherent script (with however many flashbacks) towards a fragmented and episodic structure.

Born in Belarus, educated in Kiev (Soviet Ukraine), working closely with archives in Leningrad/St Petersburg and Moscow, Loznitsa has been living in Berlin since 2001 and works in Ukraine. In 2014 he suddenly faced a dilemma about national belonging that led him to side with Ukraine in the escalating conflict with Russia. All his fiction films are internationally (co)-produced, mainly with companies in the Netherlands, Germany and Latvia (Russia contributed to In the Fog and A Gentle Creature, and here only through independent small companies), and they are made in the Russian language with (predominantly) Russian actors by a filmmaker who declares himself Ukrainian and films largely on locations in Ukraine (sometimes Latvia). The film about the Donbass, therefore, also has to be situated squarely within the director’s increasingly politicised context for his fiction films that cross an increasingly hard physical border.

At the same time, we can observe in his fiction films a shift from the observational, documentary approach to the macabre. A Gentle Creature veers off into an excessive use of the grotesque in the final, nightmarish sequence that takes up a good half hour (too much) of the film’s (excessive) running time of 143 minutes. Similarly in Donbass the obsession with the grotesque takes the upper hand as the director exaggerates each of the (re-enacted and staged) episodes to highlight the absurdity of everyday life. We know all too well that Russia, specifically Ukraine, concisely Mirgorod, is the home of Nikolai Gogol; and whilst some absurdity is inherent in everyday life, when this absurdity is turned into the grotesque, the macabre or a Monty Python show, it can easily go over the top. After all, the situation on the ground in the Donbass (the film was shot in Krivoy Rog, not far away from the conflict zone) is serious as the local population is constantly exposed to shelling and torn between different factions – pro-Russian separatists, pro-Ukrainians, so that comedy may not be quite the right register.

Donbass is composed of a series of episodes, which were inspired by blogs and amateur videos posted on the internet. Loznitsa assembled these to shape his script and re-enact the scenes with professional actors (and local extras). In an interview with Charlotte Pavard for the Cannes website (LINK https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/festival/actualites/articles/donbass-as-seen-by-sergei-loznitsa) Loznitsa comments on the approach to the script: “At some point I realised that I wanted to make a fictional film based on these real life materials. I wanted to recreate the events which took place in the Donbass in the form of a feature film. So I selected a dozen videos which I found the most striking and expressive, and wrote a script based on them.”

Whilst the scenes may be based on authentic recordings, the choice of actors to perform them is quite telling: a number of actors come from the Kolyada Theatre in Yekaterinburg, known for a demonstrative and detached acting style; then there is Boris Kamorzin, an actor from provincial Russia with deadpan performances, whom Loznitsa singles out in the above-cited interview with Pavard. But quite curiously there are also some very well-known – Ukrainian – actors whom he does not mention separately, notably Georgi Deliev and Natal’ia Buzko, both starring in the 1990’s TV series Maski- Show, and both favourites of the auteur filmmaker Kira Muratova (1934-2018), who was best known for her exaggerated portrayal of (post-Soviet) life.

The episodes tell about corruption and the theft of humanitarian aid by those in power; about a politicized wedding in Novorossiya (the name for the confederation of the two self-proclaimed people’s republics of Donetsk and Luhansk); about a municipal official who has a bucket of shit poured over him for taking bribes; about a citizen whose car is requisitioned; about a bus journey halted at a checkpoint; about the denunciation of a German journalist as a fascist; about a man identified as traitor and lynched in the street; about a well-off woman trying to make her mother come home and leave a shelter. All these scenes have a tragic core, but Loznitsa turns them into vignettes, anecdotes, farcical scenes – into performances, not for the camera but performances in real life. The assemblage is thoughtfully composed and structured, with occasional links between episodes (a video of the lynching in the street is shown at the wedding, etc.). Yet all this suffering is not only exaggerated through the acting and performed for the viewer, but also arranged for us with a very cold and detached hand. This is what allows Loznitsa to keep an upper hand for his final blow, which the viewer, however, does not get until the film’s end.

Everyday life is lawless and corrupt, and the people are deprived of essentials. However, this depravation is the result of looting and corruption by groups that assume power rather than the centre or centrally managed organisations. Therefore the sides are blurred, the fronts are frayed, and the people are not united, which makes the conflict as viewed in Loznitsa’s film look as confusing and muddled as it would look to the population, ultimately victimised not by a central authority (be that Russian or Ukrainian), but by their own people.

The final blow awaits us at the end: the episodes are framed by a scene that plays on the concept of performativity and fake news: the opening scene is set in a film crew’s trailer where several people (it seems some extras from the street, who are after some additional cash) are made up, dressed and prepared for the enactment of a scene of violence – an explosion on a bus. They are hustled to the scene, ready to perform and be interviewed about an act of violence that we may assume is also staged – for the news. At the film’s end, having contributed with their respective performances and waiting to be paid, they are rounded up in the trailer and liquidated: witnesses of staged events and fake news.

Ultimately, Donbass challenges the status of the camera as a means to capture truth, to record events authentically; it asks: is not everything here staged? Yet this challenge of the mediality of the documentary camera sometimes disappears behind the filmmaker’s relishing in the delightful performances and the colourful farces in the episodes, forgetting from time to time the overall, very pertinent issue of the reliability of stories, images, and words. At the same time, this macabre streak is what makes the film appealing and particularly resonant in the context of such spoofs as Armando Iannucci’s The Death of Stalin (2017), pulled from Russian distribution earlier this year. And while we may be able to afford such mockery to the past, it may be less suitable for the present, when there are real people living such an absurd and macabre existence.

Indeed, Donbass comes in the midst of a large wave of films about eastern Ukraine. Lithuanian filmmaker Šarūnas Bartas’ Frost (Šerkšnas, 2017) tells about a young man who – along with his girlfriend – takes a humanitarian aid truck to the Donbass and gets caught up in the violence. Russian documentarian Denis Shabaev’s Mira (2018, premiere at Sochi’s Kinotavr), is about a Slovak citizen by the name of Mira who lives and works in London, and who travels to the Donbass to visit a (female) internet acquaintance who tried to extol money from him. He stays to restore Soviet-era monuments with a group of locals. And finally, there is Renat Davletiarov’s Donbass. The Outskirts (Donbass. Okraina), Russia’s answer to films on the conflict, which premieres at the Rome Film Fest later this month (October 18-28, 2018). Are we to assume that a conflict that cannot be resolved in reality will be resolved on screen?

Crédit photo : Pyramide Distribution