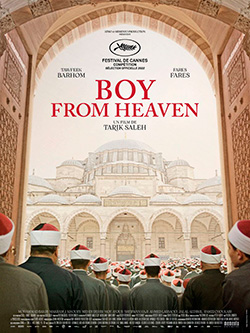

Boy from Heaven

Publié par Birgit Beumers - 31 mai 2022

Catégorie(s): Cinéma, Critiques, Expositions / Festivals

Tarik Saleh’s Boy from Heaven: Best Script Award at Cannes

Tarik Saleh is certainly no unknown quantity in filmmaking: he may be better known for his work in television, but also made a festival impact with his political thriller The Nile Hilton Incident (Le Caire confidentiel), which impressed audiences at Sundance in 2017, where it won the Grand Jury Prize. From that film, he brings Swedish-Lebanese actor Fares Fares across to the new project, Boy from Heaven, which garnered the award for Best Screenplay in Cannes.

Boy from Heaven is another well-made political thriller, but it also goes beyond a genre film with some carefully conceived imagery and, above all, a script that inverses the fairy-tale structure à la Propp in a subtle and clever manner. The film tells a story of growing-up, of the boy Adam (Tawkeek Barhom), who lives with his widowed father and younger brother in a rural area of Egypt (although the film was shot in Turkey) and earns a living as a fisherman. The family are devout Muslims, and it is the local imam who helps Adam get a place to study the Quran at the prestigious Al-Azhar University in Cairo. However, his journey to the capital and acquaintance with the big world does not open the magical space of fairy tales for him, but brings disillusionment in the world and makes the protagonist return home, but not as a rich man, neither spiritually nor materially. Rather, his return marks his withdrawal. Nothing has changed in his life after his return home, showing him in the same shabby boat catching fish with his father. We may wish to infer a religious (Christian) meaning to the opening and closing shots of a fisherman (catching souls), but in focus here is a soul that is lost. The occupation of the fisherman seems only relevant for Adam’s nickname at the school: the “sardine”.

The film manages its story of political corruption as the state seeks to gain influence over the religious world extremely well: once at Al-Azhar, Adam is quickly picked as successor to the informant Zizo, who – aware of his cover having been blown – introduces Adam to Colonel Ibrahim, a dishevelled deputy head at the Secret Service (played by Fares). Intrigues abound both within the Service (a power struggle between Fares and his boss) and outside it (the head of state wanting to influence the appointment of a new head of Al-Azhar). As different power structures within these two worlds, religious and political, try to position their candidate, the fisherman’s son and informant Adam cleverly plays the game to his advantage, ultimately securing his safe release after having witnessed the murder of the informer Zizo, uncovered a plot against a religious leader, and disclosed the work of the Muslim Brotherhood in the school. In all its complexity, the various intrigues unfold step by step, exposing the profound corruption of state and church at all levels.

Adam returns to his village at the end, having completed his university education, gained experience and matured. This is appropriate for the fairy-tale hero. However, this young man finds little magic help during his journey, but his escape from certain death comes only at the end, and it is almost miraculous. His journey may be one into a kingdom, yet it is not a magic one, but of corruption and intrigues. The miraculous release is achieved by the protagonist’s own action, through the purity of his faith and the clarity of his argument. It is this inversion of the fairy-tale model that makes the screenplay a genuinely original experiment with structure, and may explain the award for best script, supported further by the fine dialogues between Colonel Ibrahim and Adam, with the latter being lured and teased, threatened and empowered by his recruiter.

Crédit photographique : Copyright Atmo